Blog

24.02.2025, 10:00

1816 views

1816 views

None

Today Ukraine celebrates the 160th anniversary of the birth of Ivan Lypa, a Ukrainian public, political and literary figure. For us, Crimean Ukrainians, his figure is significant because he was born in Kerch. Unfortunately, the year before last, the centenary of Ivan Lypa's passing went almost unnoticed by Ukrainian society. However, it is understandable: there are more pressing problems and issues in the country today.

Ivan Lypa was born into a burghers family of a retired Russian army soldier Lev Lypa and а woman from Cossack family Hanna Zhytetska, whose ancestors supported Hetman Ivan Mazepa in his uprising against Russian imperial tyranny. In addition to their son, the couple had three daughters, Yevheniia, Mariia, and Marta: the latter worked as a public school teacher in her hometown since the 1890s and was known beyond its borders. In the summer of 1905, Marta Lypa took part in countering the pogrom (mayhem) of Jews in Kerch organized by the monarchists. More than a year later, it became known that she died during treatment in the village of Dalnyk in the Odesa region, where in 1904-1905 Ivan Lypa built a hospital for the poor.

After studying at the parochial school at the Greek Church of St. John the Baptist, Ivan Lypa entered the Aleksandrovskaya Men's Gymnasium in 1878 and graduated with honors in 1887. While studying at the gymnasium, Ivan, like his comrades, "had sympathy for everything that was oppressed" - and thus for the Ukrainian peasantry - and graduated from the school as a "convinced Narodnik", receiving a good mark in behavior because of "political uncertainty."

After spending his childhood in a dugout, Ivan Lypa got his own room in a small house at number 17 on 2nd Mitrydatska Street, where his family moved to. After the restoration of Ukraine's independence in 1991, a plaque in memory of Ivan Lypa was installed on one of the buildings on this street, but its fate after the Russian occupation of Crimea is unknown.

Describing his life in the hometown, Ivan Lypa noted that as a young man he knew

Ukrainian

so little that he did not even understand all the words in Taras Shevchenko's poems - despite the fact that in his childhood he often visited the Kuban, and also heard the conversations of the Kuban Cossacks who sometimes visited his father, and his grandmother could not speak Russian, and his father "spoke a mixture," that is, in surzhyk. At the same time, Lypa noted that in the second half of the nineteenth century, Ukrainians made up a significant part of the population of the Kerch Peninsula.

"Having never seen indigenous Ukraine, I thought for some reason that the Ukrainian people no longer existed. I looked at such works as Kobzar as the last Ukrainian word, and for some reason I was very sorry that no one knows Ukrainian anymore and cannot write like Shevchenko, Kulish, and Kostomarov did. I assumed that all this was long gone. The history of the Ukrainian people, their constant struggle for freedom and equality seemed to me like some glorious, magical fairy tale that ended forever, and the people disappeared somewhere," he said.

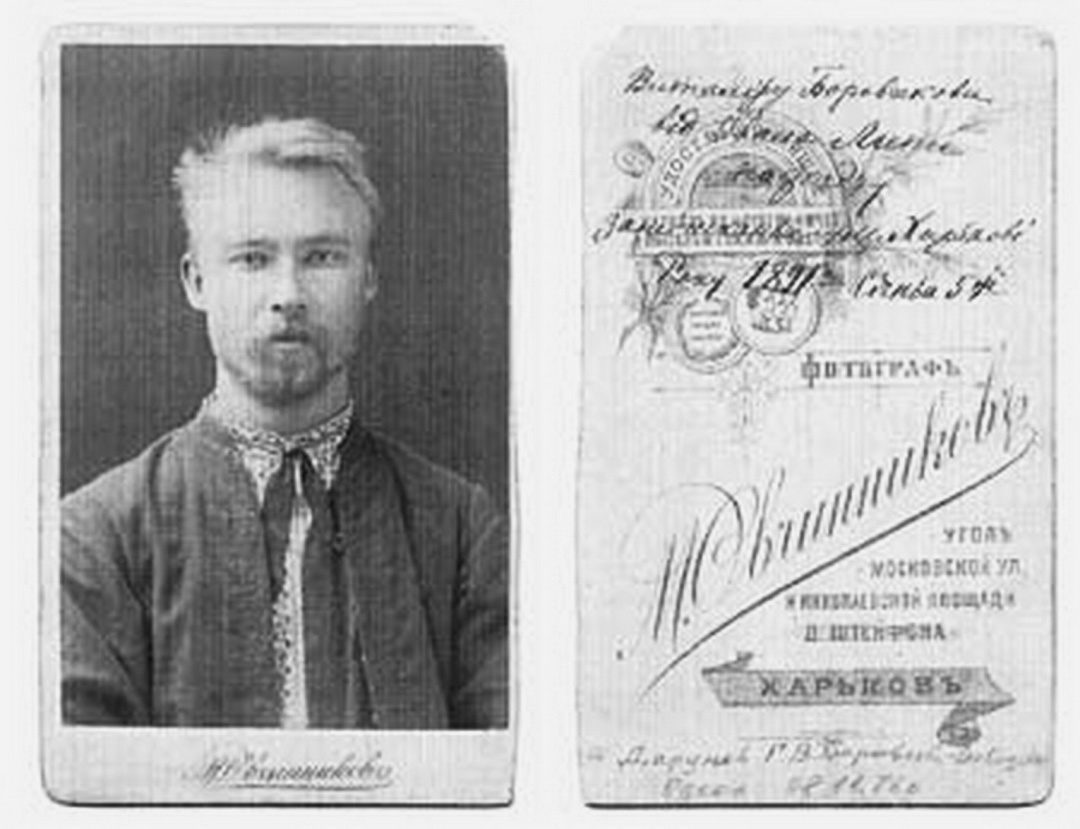

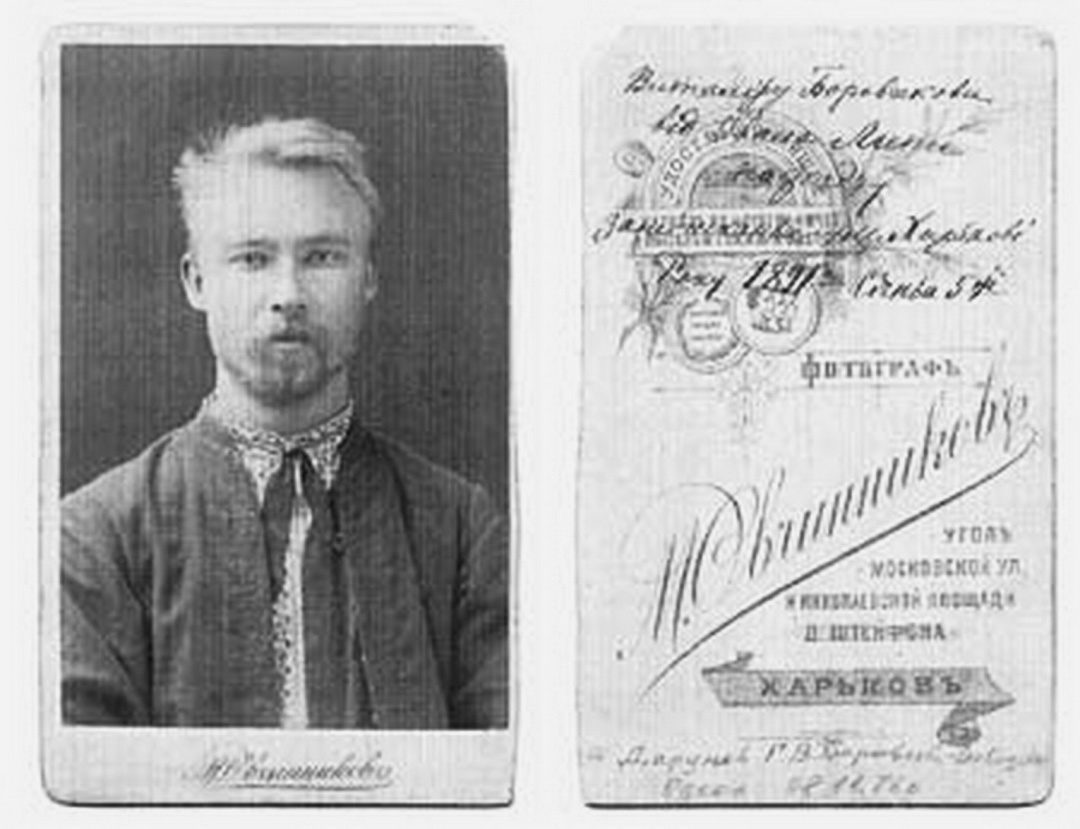

In 1888, Ivan Lypa became a student of the Medical Faculty of Kharkiv University. At the beginning of his studies, he attended a meeting of his fellow countrymen, where he heard "an essay about the existence of Ukrainian literature and the Ukrainian people," and saw Ukrainian books and magazines.

"At first I looked closely and attentively at everything, and when I was convinced that the Ukrainian people were alive, I became so fascinated by Ukrainian books that I left everything behind. My "serious" friends laughed at me, mocked me for reading fairy tales, but I did my own thing," Ivan Lypa recalled the beginning of his journey to forming his identity and beliefs.

In 1891, Ivan Lypa joined the founding of the secret society "Brotherhood of Tarasivtsi", which aimed to spread the ideas of Taras Shevchenko and fight for the liberation of the Ukrainian people. In 1893, he was arrested and expelled from the university for "striving to separate Little Russia from Great Russia," and after 13 months of imprisonment, he lived under police surveillance for three more years in his native Kerch, where he had previously periodically visited for holidays or to recover his health.

However, before his arrest, Ivan Lypa managed to do one very important thing for his native land.

In early 1892, he, already a Tarasivets and still a medical student, visited Yalta, where Stepan Rudansky, a famous Ukrainian poet and translator, city and quarantine doctor, and honorary magistrate, was buried in May 1873, before his 40th birthday. Ivan Lypa expressed a desire to see his grave, which had been forgotten for almost two decades. Fortunately, the old guard of the Polikur cemetery, who knew Rudansky during his lifetime, was able to show the way to his burial place. The poet had no relatives or friends left in Yalta at the time.

"The poet's grave is on the main alley, and the place is quite large. I looked at it and sadness enveloped my soul: no fence, no cross, just green grass and two or three trees. It would be possible to make a good fence and put up at least some monument with an inscription, but then a few more years will pass, and then no one will probably show where his body will lie. Because Yalta is a city without any traditions, without even yesterday, since most people have temporary residence there, and the rest are only chasing a penny... It will be a great pity if we lose this dear and beloved grave, as we have already lost more than one or two of them."

Ivan Lypa expressed these concerns in a note published in the Zorya magazine, which was published in Lviv,

controlled

by the Austro-Hungarian Empire

at that time. This publication had many correspondents from sub-Russian Ukraine, but it did not reach there because of the autocratic ban. The report about Rudansky's grave was published under the pseudonym "Ivan Stepovyk."

However, the active young man did not limit himself to describing Rudansky's burial and complaining about its condition. On his own behalf, he made a proposal for the Ukrainian community of Odesa, as the closest geographically to Crimea, especially since similar initiatives have already been voiced there, but at that time they were not implemented for unknown reasons.

As early as 1886, the Ukrainian writer Mykhailo Komarov, who was working as a notary in Uman at the time, submitted to Zoria a biography of Rudansky with two illustrations - his portrait and a drawing of his grave, probably by the artist Viktor Kovalyov, who knew the poet well.

Toward the end of 1892, Komarov, who was already an activist in the Ukrainian community in Odesa at the time, again noted in the Zoria that Ivan Lypa's appeal "made an impression and aroused a desire among Odesa fellow countrymen to arrange the grave of the poet." As a result, "an inexpensive but quite beautiful monument" was erected in Yalta for the funds raised at events dedicated to the anniversary of Taras Shevchenko and for the sold portraits of Rudansky.

In the early 1910s, Rudansky's grave was described as "completely neglected and abandoned" - despite the fact that a large number of Ukrainians constantly lived in Yalta, and representatives of the Ukrainian intelligentsia periodically visited the city. At different times, the poet's grave was visited by Oleksandr Konysky, thanks to whom we know the original appearance of the monument on the poet's grave, Yevhen Vyrovy, Serhiy Yefremov, and others. In 1913, in the Yalta magazine Russkaya Riviera, members of the city's Ukrainian community shared their plans to improve Rudansky's grave and install a fence on it but World War I prevented them from doing so: Ukrainians in the territories controlled by the Russian Empire were forced to go underground. It was only in mid-April 1917, after the overthrow of the autocracy, that the Ukrainian community revived in Yalta, and a commission was established to patronize the grave of Stepan Rudansky. Using the funds raised,

commission

members bought the land plot with the poet's burial place from St. John the Baptist Church, but there was not enough money to install the fence. On May 3, 1917, the first known celebration in memory of

Stepan Rudansky

took place at his burial site, under the Ukrainian flag.

I had the opportunity to describe the detailed history of Stepan Rudansky's grave to the present day in a detailed note in a corresponding article, so I would not like to repeat myself. Also I've got the chance to recall some episodes of this story, as well as the personality of Ivan Lypa, with my colleague and fellow countryman Andriy Ivanets in the program "Na Chasi" for Ukrainian Radio.

I remember then I made an assumption that I periodically voice in the circle of my associates: if we are ever destined to see our native Crimea in the Ukrainian space again, we will come there on scorched earth. Hope that it will not be literally scorched, but only in humanitarian terms, since we risk not finding anything Ukrainian there.

However, it is possible to prepare proper soil on the scorched earth and grow grains on it. We can restore our heritage and honor our dead and fallen with dignity.

But for this, we need personalities like Ivan Lypa.

1816 views

1816 views

The published material is copyrighted. The opinions expressed in the author's blog may not coincide with the position of the editors of the «Voice of Crimea» IA.